South African law needs to develop and quickly catch up with the risks that generative AI poses so that we can safely exploit the far-reaching benefits and opportunities it offers.

Have you ever wished you could transplant your brain — all your experience, knowledge and intuition — into a machine and get the output you need, productively and time efficiently?

In business, the concept of the billable hour is inherently self-limiting — there is a restricted number of billable hours in any day and we all need time to spend with family and friends, get enough exercise and sleep, as well as free time to remain vaguely pleasant human beings.

But imagine being able to have the answers to clients’ queries drafted, go for a run and tell your partner what type of pasta you would prefer them to buy for dinner (the much-debated “mental load” placed on women, in particular) at the same time — without having to consciously be present for each of those activities. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) could make this a reality.

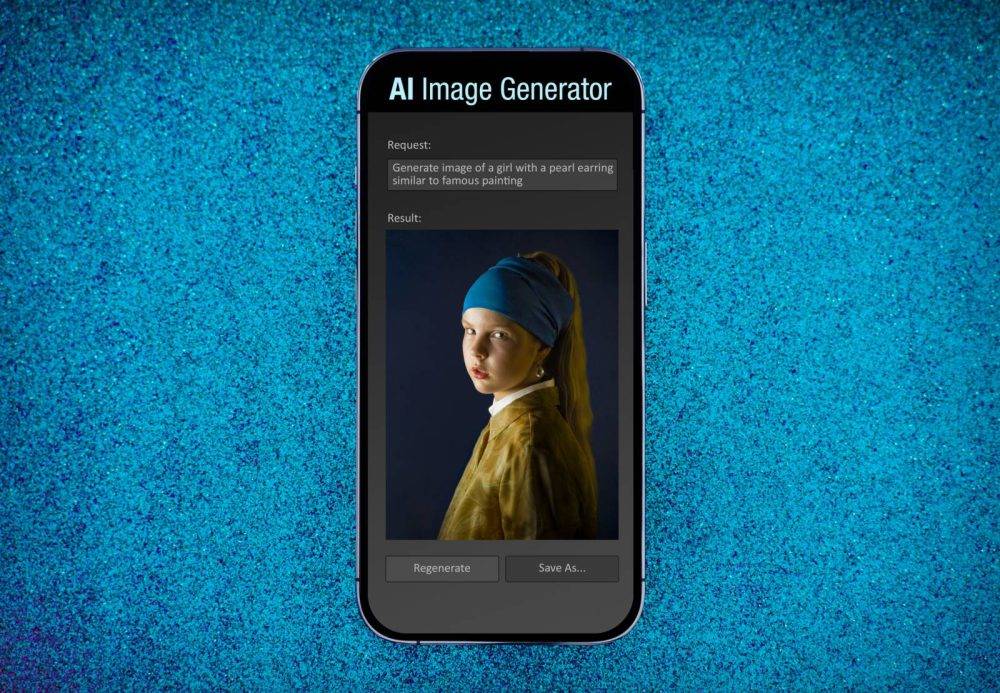

Generative AI is different from previous forms of AI because it can generate new things rather than identifying or grouping/ classifying what it has seen before. Put simply, generative AI can consider a set of examples and put together the patterns and rules that it detects to create a new example of its own. We can train it using our unique style of communication and it can generate responses that mirror our personal voices.

One of the current uses of generative AI is to duplicate someone’s image or voice. Another is to generate new creative output based on someone’s unique style, for example, a piece of art or writing. This has been the subject of much concern in the creative arts industry as well as in the fields of journalism and creative writing.

The 2023 screen actors’ and writers’ strike in the US was primarily concerned with the use of generative AI, particularly digital replicas, by TV and movie studios. The deal ultimately struck between the unions and the studios included guardrails against the exploitative use of generative AI, such as consent to the use of a digital replica at the time of use and fair compensation.

The ongoing litigation in the US over the use of The New York Times’s articles to train GPT large language models is another example of how protecting individual creative output and technological innovation are already butting heads.

On the other hand, Generative AI presents huge opportunities to solve another societal issue — striking a work-life balance.

Despite, or maybe because of, advances in technology, people are spending more time than ever working. To be able to create a duplicate of yourself, to answer emails and questions while you attend to other aspects of life, is an enticing thought and could free you up to actually achieve work-life balance without sacrificing career development and earning potential.

What about sending a duplicate of yourself to a virtual meeting and having it report back while you are at a doctor’s appointment during the week? The possibilities seem endless. Already many are using Chat GPT and other generative AI functions to train their own “assistants” who can conduct tasks for them, such as meal planning and sorting through their inbox, in the same way that they would.

But, as we have seen with the creative arts, responsible use of generative AI is required to ensure the protection of rights.

The concept of the ownership of creative output is not new to the law and an entire body of intellectual property law has been developed in South Africa to cater for the protection of creative and other original works and balance the competing interests in this regard.

But generative AI, and the creation of digital replicas, present a new challenge to the country’s legal framework, which it was not necessarily designed to meet. The concept of a digital replica of an individual does not fit neatly into the types of original works subject to intellectual property law and might be better regulated under privacy laws.

There are also increasingly sinister and dangerous uses of digital replicas, one example being the use of “deepfakes” using a digital replica of someone in a degrading or humiliating manner and spreading it across the internet — think the Taylor Swift deepfakes posted on X and Telegram earlier this year.

South African law needs to develop and quickly catch up with the risks that generative AI poses so that we can safely exploit the far-reaching benefits and opportunities it offers.

On 15 October 2024, it was announced that President Cyril Ramaphosa had referred the Copyright Amendment Bill and the Performers’ Protection Amendment Bill to the constitutional court to address the constitutionality of certain provisions.

The court previously ruled that the Copyright Act was unconstitutional and ordered parliament to amend it. The Copyright Amendment Bill includes an exception from copyright protections for “fair use” and scholarship, teaching and education, as well as extending the rights of authors, artists and performers.

The concept of “fair use” is found in legislation in the US and will be central to The New York Times litigation.

Some have suggested that the Copyright Amendment Bill presents an opportunity to cater for, and clarify, the conceptual challenges posed by generative AI in the intellectual property arena. The outcome of the New York Times litigation could serve as a useful guide to South African legislators and courts when faced with determining the limits of fair use in the context of generative AI.

Rachel Potter is a senior associate, and Vanessa Jacklin-Levin a partner, at Bowmans South Africa.