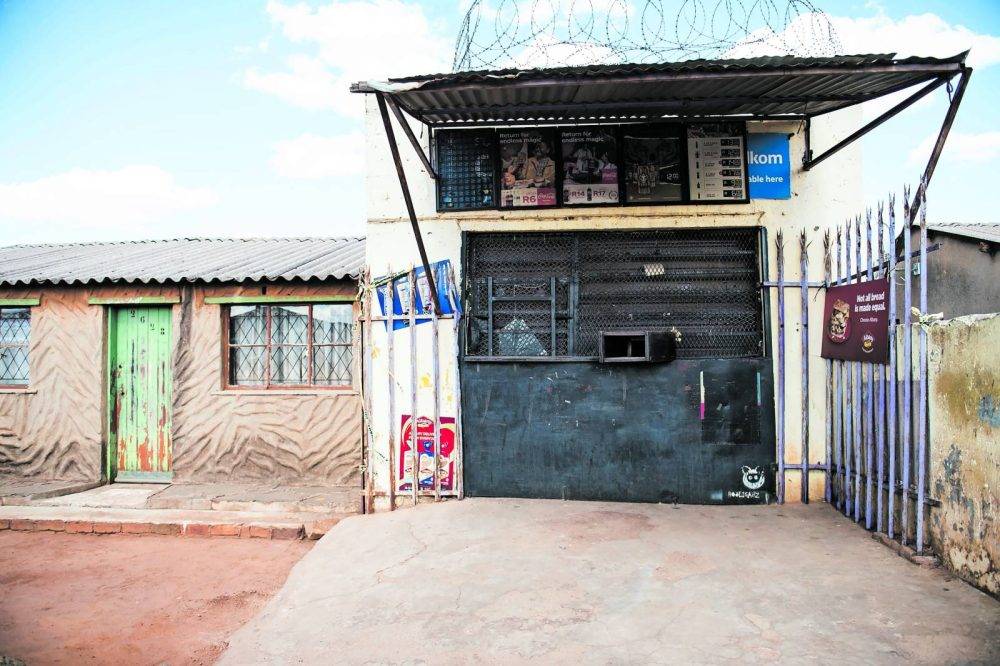

All spaza shops are now required to register with their local authorities. However, this raises a critical question about the effectiveness of current quality control measures in protecting consumer safety. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

South Africa has about 532 townships, where more than 40% of its urban population resides. In 2019, these townships had about 21.7 million residents, with Gauteng having the largest population at 8.9 million.

These townships stem from the policies of the apartheid era, specifically the Black Communities Development Act of 1962.

Townships are usually on the outskirts of cities, far from the opportunities and resources available to others. High crime rates, poverty, unemployment and inadequate service delivery persist. Township residents face an additional pressing concern, the alarming rise in food poisoning and foodborne illnesses, which threaten food security and residents’ health and well-being.

Food poisoning is not an unprecedented issue in South Africa. There have been numerous incidents caused by consuming unsafe food over the years, including that sold in spaza shops.

For example, in 2021, a student from Tshepisong in Roodepoort died after allegedly eating biscuits she bought from a spaza shop and, in Kagiso, 29 people were rushed to the hospital after suspected food poisoning, which resulted in two deaths, after eating food served at a funeral.

Also in that year, in Mpumalanga, two siblings died allegedly within an hour of eating noodles. In the same period, three Eastern Cape children, aged 11, seven and six months, reportedly started feeling ill after eating a packet of noodles and died on their way to hospital.

Since the start of September 2024, 890 incidents of foodborne illness have been reported in South Africa.

Worldwide, more than 1 billion episodes of food poisoning-related diarrhoea occur annually, leading to the deaths of about 3 million children a year, mainly in underdeveloped regions.

This stark reality underscores a public health crisis that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations in impoverished and under-resourced areas. Many township residents can’t afford to buy fresh vegetables, fruit and properly stored food.

Structural violence is an insidious and pervasive form of violence that operates beneath the surface of broader social, political and economic structures. Unlike physical violence, which is immediately visible and tangible, structural violence is often invisible, yet no less destructive.

In South Africa, structural violence is linked to the policies of the apartheid regime. This legacy of oppression has contributed to the chronic neglect of townships, rendering their problems invisible and unworthy of government intervention.

The stark contrast between the treatment of township residents and affluent suburbanites is telling. Supermarkets in wealthy areas suspected of selling unsafe food would be shut down and policies and regulations governing food safety and quality would be enforced.

All spaza shops are now required to register with their local authorities. However, this raises a critical question about the effectiveness of current quality control measures in protecting consumer safety. Moreover, this registration will be ineffective if frequent food inspections are not carried out.

This raises another important question — does registration merely provide a veneer of legitimacy, allowing these supermarkets to continue selling hazardous products, albeit legally?

It is perplexing that the government fails to enforce policies and regulations such as the Consumer Protection Act, which safeguards consumers’ rights to fair value, good quality and safety. Similarly, the Cosmetics, Disinfectants Act, which promotes personal and environmental hygiene in food handling, remains largely unenforced.

The root causes of food safety issues and foodborne illnesses are well-documented: inadequate food safety practices, poor sanitation and poor hygiene. In townships, these problems are exacerbated by structural violence, the lack of enforcement of food safety laws and regulations, coupled with ineffective inspections by government authorities.

The local government should immediately act against anyone selling, manufacturing and importing contaminated and poisonous food. People who conduct business or handle food should ensure that the storage, cooking, preparation and handling is hygienic.

Since 2021, the department of health has run a campaign urging consumers to be vigilant when buying food, for example, to ensure that the packaging is not damaged, to check the expiry date and only purchase from reputable companies.

The public is also encouraged to practice good hygiene when handling food and to report any suspicious products to the local authorities so that investigations can be carried out to stop the spread of foodborne illnesses.

Although the informal economy supports the daily livelihoods of many of the poor, the consequences of unregulated sale of food can be dire. The frequency of foodborne disease outbreaks is alarming, yet many incidents remain shrouded in silence, with many going unreported.

Lemeese Steyn and Stanley Muravha are Master’s Students at the Department of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg.