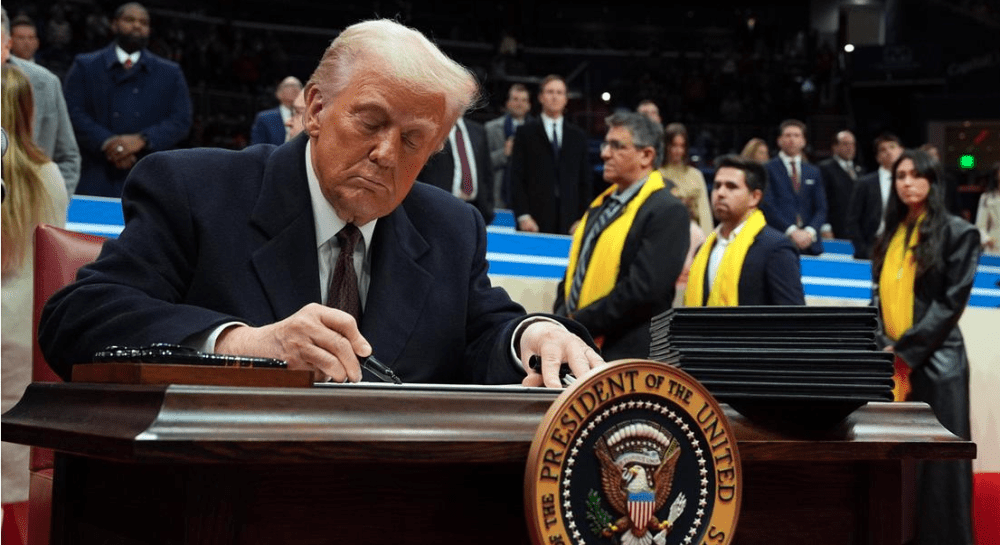

US President Donald Trump. (Evan Vucci/AP Photo/picture alliance)

On 14 March 2025, in what has become the de facto method of governance for right-wing populism, US Senator Marco Rubio declared on X that South Africa’s ambassador to the United States, Ebrahim Rasool, was “no longer welcome” in the country. Rubio’s pronouncement — devoid of diplomatic process or official sanction — was as sudden as it was arbitrary, another dispatch from the Trump administration that now operates primarily through shock-and-awe tactics rather than any structured institutional process.

Rubio’s statement raises fundamental questions: can a tweet dictate foreign relations? Has the democratic machinery of the US now been entirely supplanted by the all too astute exploitation of social media algorithms? And, crucially, what does this spectacle mean for the rest of the world, particularly those nations caught in the crossfire of Washington’s increasingly erratic, reckless and dangerous pronouncements?

Guy Debord, a 20th-century French philosopher and Marxist theorist, one of the most influential critics of modern media and capitalism, described contemporary political life as a spectacle, where governance is above the endless production of images, performances, and distractions rather than substantive processes of deliberative decision-making. His seminal work, The Society of the Spectacle, argued that modern life had been transformed into a series of mediated images that distort reality, pacify the public and reinforce existing power structures.

The removal of an ambassador by tweet is not about diplomacy; it is about political theatre. It is a crude assertion of dominance, an attention-grabbing headline that feeds into an already over-saturated media landscape, designed to provoke outrage, not engagement. Trump, both in and out of office, has perfected this mode of governance. His administration, and now his political resurgence, is a case study in the society of the spectacle — where declarations of economic war, diplomatic expulsions and attacks on social progress are all animated as well as expressed through social media. The substance of governance disappears behind the glare of the screen, and reality itself is dictated by the most viral pronouncement of the day.

Some of this is not new. Imperial powers have long relied on intimidation, overwhelming force and propaganda to maintain their authority. The Romans staged grand spectacles — gladiatorial combat, triumphal marches and public executions — not merely as entertainment but as instruments of political control. The British Empire ruled through the pageantry of monarchy, the relentless performance of colonial superiority and the imposition of a bureaucratic order that disguised brute force. Hitler’s Nazi regime mastered the use of spectacle to manufacture consent and eliminate opposition, employing grand rallies, mass propaganda and tightly controlled media to create the illusion of unity and inevitability.

What makes today’s politics of spectacle different is its speed, reach, acceleration and transience. Whereas historical empires constructed enduring narratives of power, the US under Trumpian politics operates through a relentless churn of shock events, each designed to eclipse the last. The goal is not stability or even control but the permanent destabilisation of public discourse, making governance itself a rolling crisis.

This transformation of politics into spectacle is not solely the work of politicians. Tech oligarchs such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are active participants. They provide the stage for this new political theatre, profiting from the outrage cycles that keep users engaged. The relationship between tech monopolies and Trumpism is symbiotic: the more incendiary the statement, the more engagement it generates; the more engagement, the greater the profits for tech capital.

But unlike the dictatorships of the past, this new form of governance does not centralise power in a single individual. It operates through diffuse networks, where viral outrage replaces political organisation, and demobilisation is the inevitable outcome. In the spectacle-driven world, political engagement is reduced to reacting, liking, sharing — but never organising or acting.

What happens when governance becomes a performance? The audience — no longer citizens — becomes exhausted and numb — a state Debord described as the alienation of modern life. The more we watch, the less we feel in control of our world, and the less likely we are to organise and resist.

Yet the consequences of rule by tweet are all too real. The defunding of USAid programmes left thousands of global health and education projects in limbo. Trump’s online rhetoric to immigration produced material forms of oppression in the form of mass raids by ICE abruptly disrupting families and workplaces. Declarations on X are performances, but they ripple into material reality, often at great human cost, as the machine keeps turning, fuelled rather than unbothered by the outcries of the moment.

How do we respond to this new form of power in which politics is enacted as entertainment, as public displays of power? First, we must recognise it for what it is: an illusion designed to distract and exhaust. Trump’s declarations matter, but they are not diplomacy, law or reality. They are performances of power, and performances can be interrupted.

Second, we must remember that engagement is not resistance. The cycle of likes, shares and comments drains energy, fuelling an outrage machine that thrives on reaction but delivers no real change. Social media repackages anger as performance and counter-performance, turning users into spectators rather than agents of action. True resistance happens beyond the screen — through organising, mobilising and building alternative spaces that challenge power on their own terms. Building material forms of counter-power is essential.

History offers an encouraging lesson: empires built on spectacle collapse under the weight of their own illusions. Empire is vulnerable when its spectacle of power outstrips its material forms of power. Rome’s grandeur gave way to its internal contradictions. The British Empire, for all its flags and ceremonies, was undone by its inability to sustain economic and political control. The US, despite its century of dominance, is a newcomer to the global stage. It is not invincible, and its spectacle is not eternal.

The Luddites, often mischaracterised as mere machine-breakers, were fundamentally concerned with the socio-economic implications of technological advancements. Their actions were not a rejection of technology itself but protest against its use to exploit workers and erode their livelihoods. As historian Eric Hobsbawm noted, their machine-breaking was a form of “collective bargaining by riot”, a tactic to pressure employers and foster worker solidarity in an era when traditional forms of negotiation were unavailable.

This historical perspective offers valuable insights for our contemporary engagement with social media. Instead of allowing these platforms to dictate our interactions and perceptions, we can repurpose them as tools for genuine organisation and resistance. But this requires much more than performances of anger, or virtue. It requires consciously directing our online activities toward meaningful collective action. We must harness technology to serve our interests, much like the Luddites sought to assert control over the industrial forces reshaping their world.

The imperative is not to “break the screen” but to transform it into an instrument of empowerment. By doing so, we challenge the passive consumption of spectacle and actively participate in shaping a more equitable digital landscape. As Debord reminds us, “The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.” The question is not whether we should abandon social media, but whether we can repurpose it as a tool for real-world resistance, ensuring that our actions extend beyond the screen and into the spaces where power is actually contested.

Vashna Jagarnath is a historian, labour consultant and Pan-African and South Asian socio-political specialist.