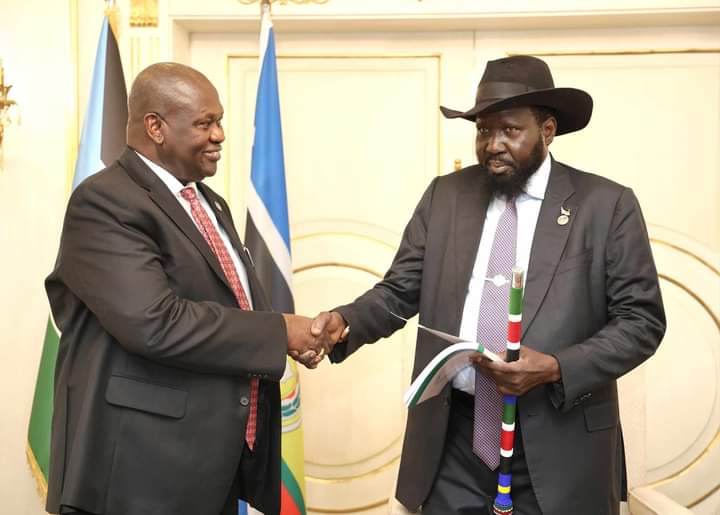

Salva Kiir and Riek Machar hold the nation’s fate in their hands. Again. (X)

Fifteen years into its independence from the north, South Sudan is at a precipice — will it slip back into war or pull back and fully implement the 2018 agreement that ended its first civil war? President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar agreed to share power — but not much sharing has happened.

And now, in the country’s Upper Nile State, bullets are flying again and bombs are dropping. Kiir and Machar are once again on opposite sides.

At the beginning of last week, more than 20 civilians were killed in aerial bombardments of Nasir, a town near the Ethiopian border in Upper Nile. Local residents accused the armies of South Sudan and Uganda of doing the bombing, alleging that residential areas were deliberately targeted. Even though Kiir and Machar are in theory both leaders of the government, state forces and their allies, like Uganda, are seen as serving Kiir.

Earlier this month, government forces had left Nasir amid attacks from the White Army, a militia predominantly composed of Nuer people loyal to Machar. In the most publicised incident, a UN helicopter evacuating people from Nasir was shot at, killing a crew member and critically injuring others. The hostilities escalated days later when the White Army executed General Majur Dak, an officer of the South Sudanese army who had been captured.

President Kiir has since joined arms with the Ugandan army to fight the insurgents. Blaming Machar, Kiir has arrested or sacked many of his vice president’s government allies and reinforced hostile security around his home.

In theory, Kiir and Machar are in the same government and are in the same political organisation, the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). Machar’s faction is called SPLM in opposition (SPLM-IO).

The violence in Upper Nile first flared up when the government announced plans to replace long-serving soldiers with new recruits. Local militia fighters who have long demanded to be fully integrated in the national army now face forced disarmament and reject the government’s plan.

Creating a unified national force was agreed in the 2018 power-sharing agreement between Kiir and Machar but it has not happened. That delay means that there is some public sympathy for Machar’s camp — even as its fight is waged by a militia that has a notorious history of ethnic violence.

Above all, nobody but the belligerents wants a return to full-scale war. The SPLM-IO’s recent announcement that it is pulling out of the 2018 peace arrangement has heightened anxiety.

“The opposition should protest the arrest of their leaders but not pull out. Now there’s a clear sign that the government may not yield to the IO’s demands, increasing the likelihood of war,” says Dr Abraham Kuol Nyuon of the University of Juba.

A coalition of the embassies of Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the UK and the US in Juba recently offered to mediate direct talks between Kiir and Machar.

Earlier attempts — including efforts led by the regional bloc Intergovernmental Authority on Development, peace talks in Rome and negotiations in Kenya and Ethiopia — did not advance the power sharing enough to prevent the current escalation.

Yet, the alternative is horrific. In 2015, when disagreement between Kiir and Machar escalated into a civil war, an estimated 383 000 died in the three-year conflict and the country was thrust into the 2017 famine which affected 6 million people.

Even with that recent memory, the two sides are not ruling out a return to war. Defence Minister General Chol Thon Balok said: “If IO doesn’t dissolve the White Army, we shall fight.”

General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the head of Uganda’s armed forces, the UPDF, said: “I want to offer the White Army an opportunity to surrender to the UPDF force before it’s too late. We seek brotherhood and unity. But if [they] dare to fight us, you will all die.”

But people directly affected by the violence strike a different note.

“Both parties must stop. Let the cycle of brutality end. My heart is broken,” Abul Majur, daughter of the slain South Sudanese army general Majur Dak, said in a statement.

This article first appeared in The Continent, the pan-African weekly newspaper produced in partnership with the Mail & Guardian. It’s designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download your free copy here.